Athens Books to Prisoners fights the system to get inmates books

Currently more than 2 million people in the country would have to go to great lengths to read the very article you are reading right now, if they aren’t totally restricted from accessing to begin with.

There are no explicit discriminatory restrictions that bar specific populations in this country from accessing information. Yet there is a body of people, roughly equivalent to the population of Chicago, that has little to no access to information because they are incarcerated by the United States government.

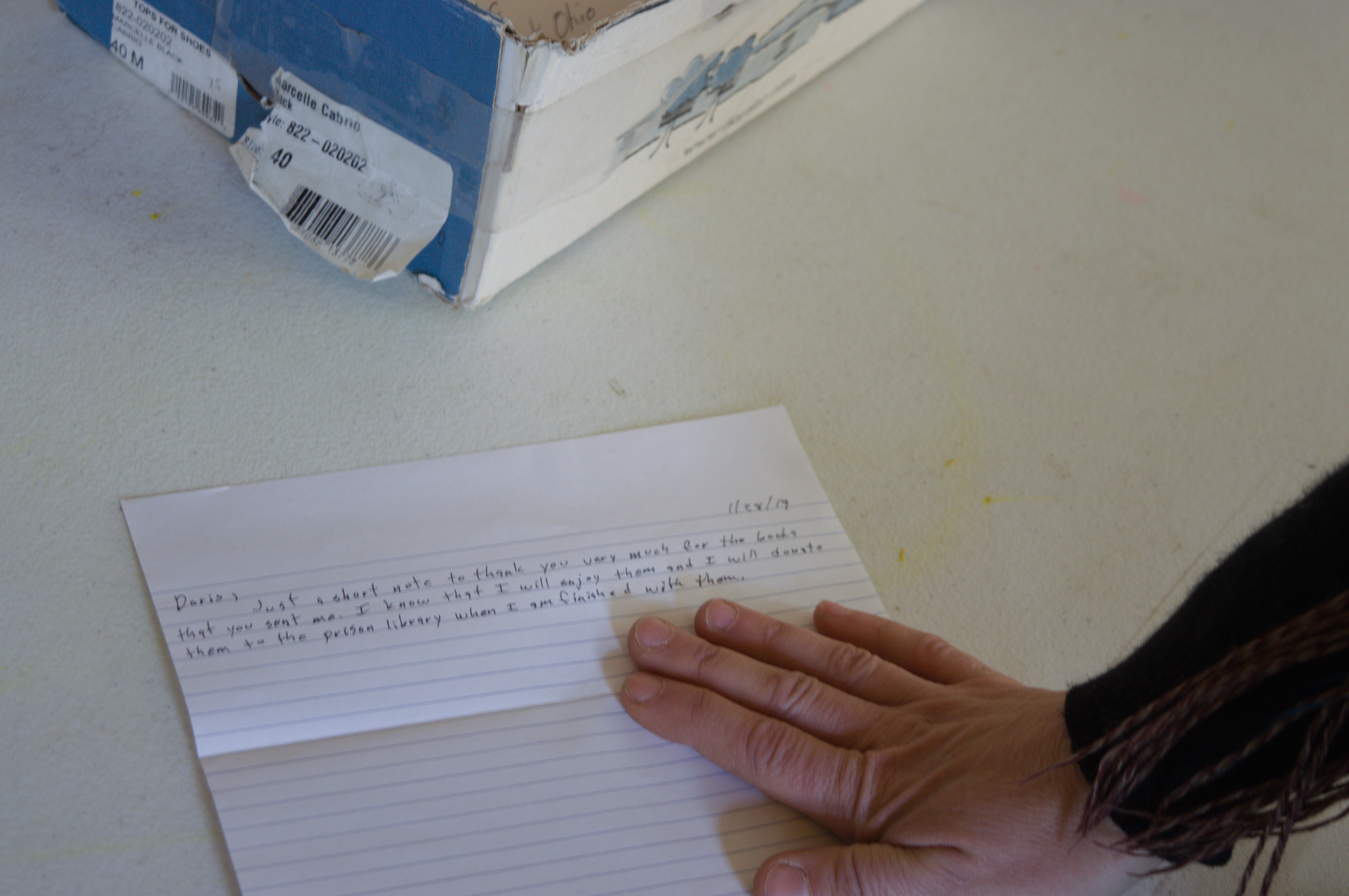

“It seems like some people want to believe that if someone is incarcerated, they don’t deserve help, or books, or enjoyment,” says Sarah Fink, as she sorts through a pile of handwritten letters sent from prisons around Ohio.

Fink, along with her friend Caty Crabb, founded Athens Books to Prisoners (ABP), a volunteer-run organization based in Athens, Ohio that ships books to prisons around Ohio upon inmates’ requests. The organization aims to help redress the lack of resources available to incarcerated people.

Many of the envelopes Fink thumbs through have been visibly opened and resealed, inspected by the prison mailroom before being approved for delivery.

“Many of the requests we receive are from prisoners with little or no access to adequate prison libraries or educational programs. [ABP] is a community-based direct action response to that problem.”

Athens Books to Prisoners Mission Statement

The right to access information in America feels so inalienable to those living on the outside of prisons, it’s normalized to a point where it isn’t thought of as a privilege not afforded to all. The U.N.’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states the public’s fundamental right to freedom of expression includes the freedom “to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

At the turn of the millennium, this became even more feasible, with the rise of information technology and access to the internet, for those who can afford it. And for those who can’t, public libraries still exist and bridge that gap. These government-funded free-to-all libraries provide internet access, entertainment, educational programs, large varieties of media formats of different genres, and a quiet environment to work, or simply exist. These are essential services for people who are poor, disenfranchised, or otherwise marginalized– identities which disproportionately crossover with the incarcerated population, but they aren’t granted the same facilities.

Despite generating a multi-billion dollar revenue annually, the prison system bolsters libraries that are lackluster at best— often sparse, and filled with out-of-date, damaged, and irrelevant reading materials. Prison libraries rely heavily on donations from individuals and volunteer groups, but many, like ABP, opt to mail books directly to inmates instead.

“Being imprisoned in incredibly dehumanizing. You barely get to own your own body in prison. We’re helping people rehumanize themselves by giving them property. They get to have a book that’s their own belonging, and they get to decide what happens to it. After they’re done reading it, they might decide to mail it to a family member on the outside, or give it to another inmate to read, or donate it to the prison library,” Fink says. “The fact that they get to own that book is important.”

Fink and Crabb met in Athens, a rural Appalachian town along the Hocking River. It’s most commonly known for being the home of Ohio University, a large public school with an enrollment of around 23,000 students, roughly the same number of permanent residents in Athens. Both Fink and Crabb worked with books to prisoners volunteer groups in other states, and wanted to start a similar organization in Athens.

“What finally allowed us to found ABP was some friends offering us free rent in a room in their house, which took the burden of fundraising for a place to store books off of us,” says Fink.

That house has remained the operational headquarters for ABP since 2010 when it started. The small house, with its rust red door and chipping blue paint, is nestled in a tightly-packed line of a hodgepodge of equally characteristic residences. The pothole-ridden one way street sits at the bottom of an impossibly steep hill and an old vast cemetery, two notoriously common features of Athens. The house’s porch is filled with brown cardboard boxes of used books. Volunteers come here every other week to carry out the organization’s functions.

The way the organization works seems pretty straightforward in theory— inmates write letters to ABP requesting specific titles, authors, or genres, and volunteers scour the headquarters’ library for the closest match, and mail them back. But in reality, books to prisoners programs across the country face many obstacles. Organizations must adhere to each facility’s unique restrictions on what kinds of materials they will accept, and if they don’t, the donated materials may be destroyed or mailed back, and the organization must foot the shipping cost.

Facilities constantly and arbitrarily change their rules, and don’t necessarily notify the public when they do. Some facilities have pretty simple rules, like no hardback books, and other are more complicated, like a list of hundreds of specific titles that are not allowed. Texas released a list of 10,000 titles banned in its state prisons: “Where’s Waldo” is prohibited, but Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” is allowed.

Volunteers at the ABP headquarters pass around a double-sided sheet of paper with a list of all the prisons and jails in Ohio and their unique restrictions on accepting reading materials. The page is covered in handwritten annotations, crossing out, and rewriting the information over and over again to reflect the changing rules. “NO HARDBACK.” “3 BOOKS MAX.” “EACH BOOK CANNOT EXCEED MORE THAN 11 IN NOR WEIGH MORE THAN 2LBS.” “NO SEX.” “NEW BOOKS ONLY.” “ NEW OR NEW-ISH BOOKS ONLY. ” Some facilities are unfortunately blacked out, meaning they’ve stopped accepting books entirely.

“There are only two women’s incarceration facilities in Ohio, and both have eventually banned sending books and other materials directly to prisoners. At one point, we were allowed to send them new dictionaries and composition notebooks, but that was banned as well, because the prison wanted inmates buying those materials from commissary.”

Sarah Fink, founder of Athens Books to Prisoners

Now, the only way for ABP to serve incarcerated women in Ohio is to drive carloads of books to the prisons to be donated directly to their libraries.

“It’s not how we want to be doing things, but it’s the only thing we can do,” she says.

ABP relies exclusively on donations and volunteers to keep the organization running. Their library is stocked by individual donations, donations from bookstores, and books leftover from sales at public libraries. Because of this, they aren’t able to always give people the materials they request. Self-help, how-to, and spirituality books are some of the most commonly requested materials that ABP does not always have enough of.

Volunteers can be seen scooting past each other in the living room turned library of the ABP headquarters, letters in hand and scouring the shelves for the requested material. Vi Ritchie, one of the volunteers, squeezes between the sci-fi/fantasy shelf, and the how-to shelf, a gap that couldn’t be much more than 12 inches, to look for a book on carpentry.

“I wish we could give people the exact titles they want, but I think they would still appreciate whatever we can send if we can’t do that.” Ritchie recently began volunteering with ABP, after hearing about the organization through word of mouth, and aligning with their mission, which is how most of the organization’s repeat and regular volunteers come to learn about its existence.

However, many of the volunteers at the biweekly book packings are students at the university who are looking to complete community service hours for their sororities and fraternities.

“I think this is really important work, and anyone who cares about the importance of books and their accessibility could find meaning in volunteering here,” says Ritchie.

“People who are incarcerated are some of our most vulnerable people because they can’t help themselves,” says Fink. “We hope our work can take some of the burden off them and their loved ones.” Fink holds onto a number of thank you letters inmates have sent, giving some validation that the organization is impactful in the ways she wants it to be.